How to Build AI Agents: Inside Out

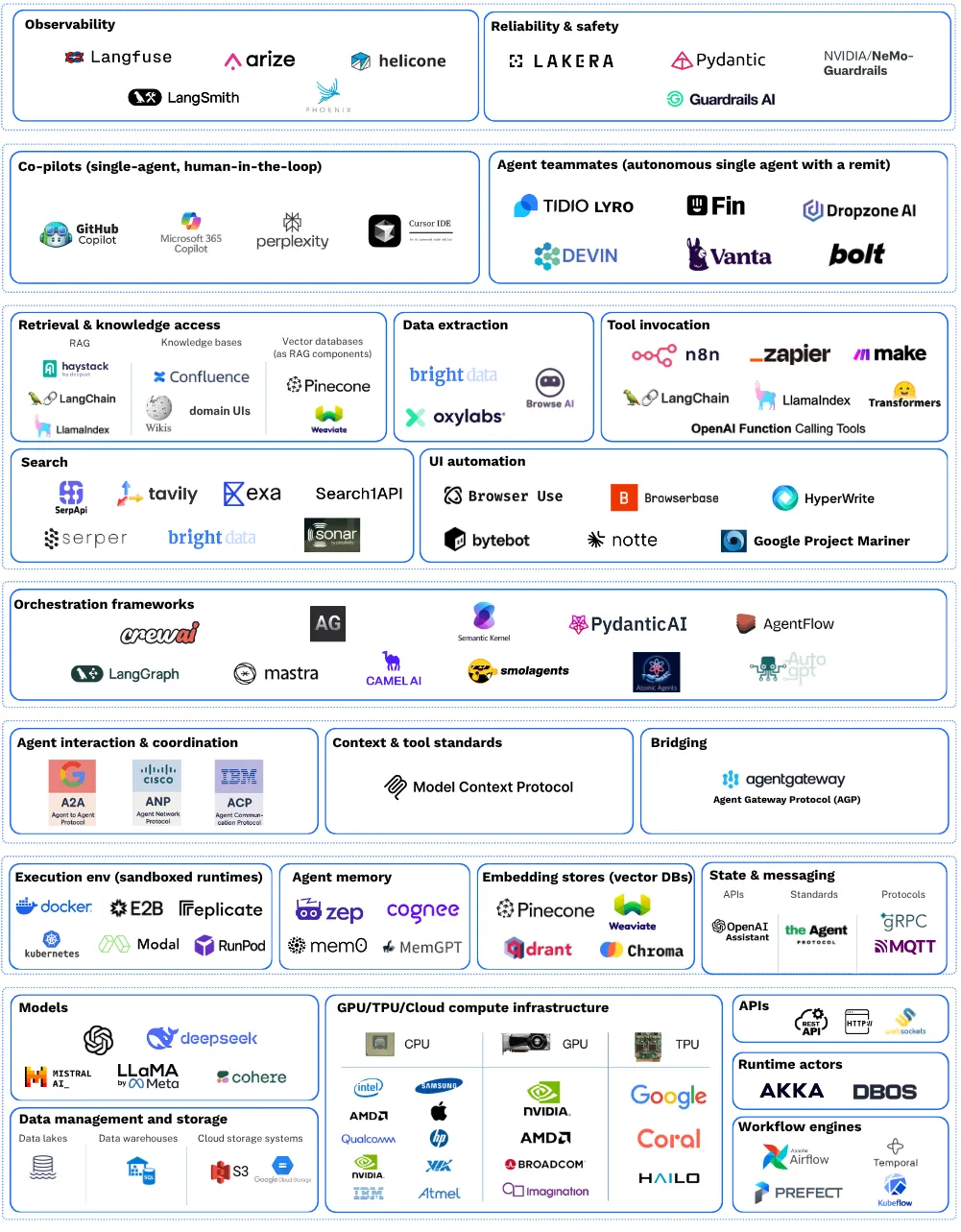

Every agent framework gives you the same pitch: here are your primitives (tool calling, structured output, orchestration graphs), now go build something. Pydantic AI, OpenAI Agents SDK, LangGraph, Google ADK. They all hand you blocks and wish you luck with the loop.

The problem is that multi-step agents need more than blocks. They need tool sequencing that adapts to intermediate results, state management across steps, cost and token budgets, error recovery, and session management. The framework gives you the pieces; you build the glue that holds them together. And that glue is where the brittleness lives.

Every framework demo is three tools called in sequence. Real agents branch, retry, backtrack, and adapt. The more steps your agent takes, the more orchestration code you write, and the more fragile the whole thing becomes. You end up spending most of your time on plumbing rather than on the behavior that makes your agent useful.

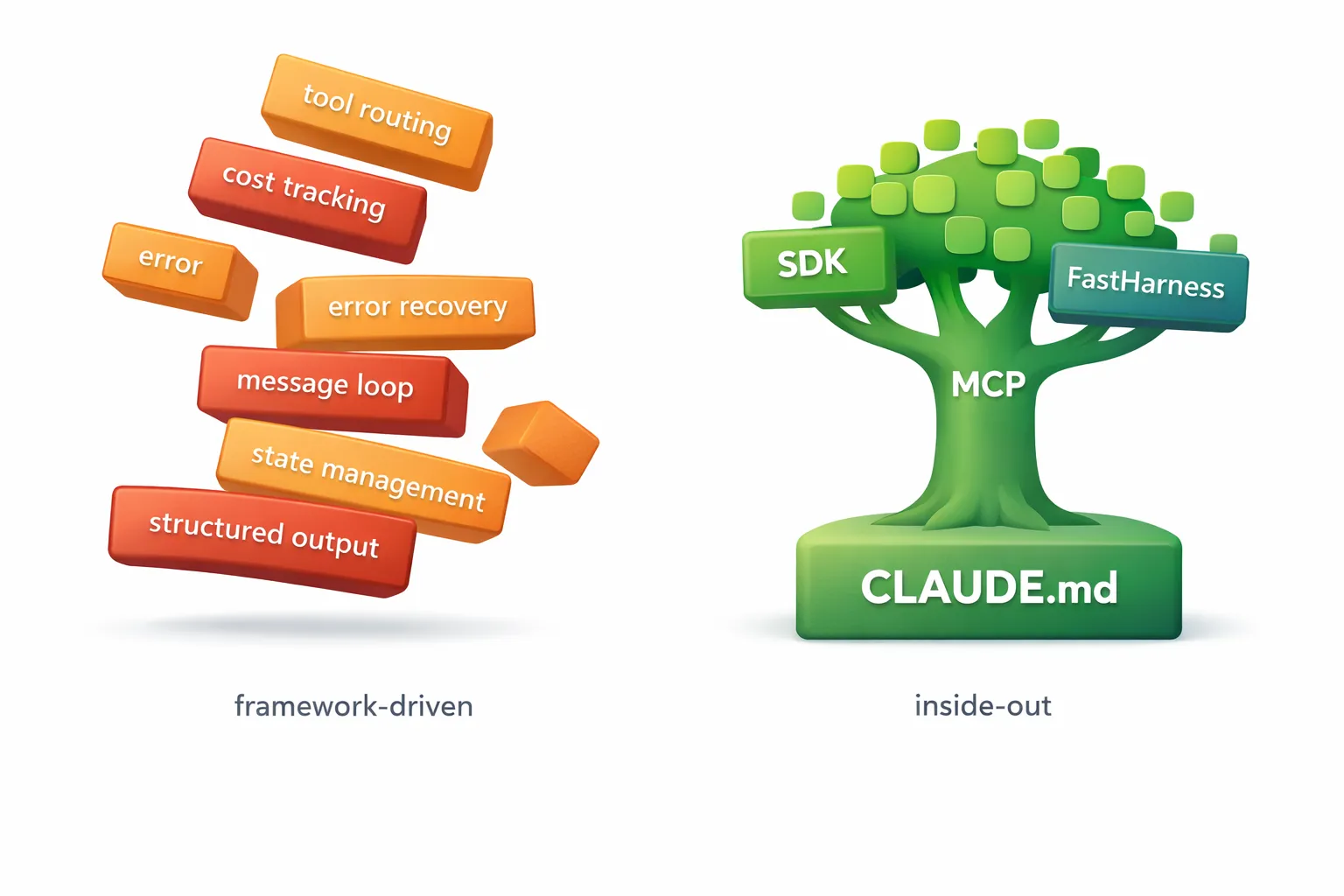

I’ve been building agents for the past several months, and I’ve converged on a process that inverts the usual approach. Instead of starting with code and working inward toward behavior, I start with behavior and work outward toward code. I call it the inside-out method, and it has four stages.

What if the loop already existed?

The reframe that changed my approach: Claude Code is already a multi-step agent runtime. It handles tool sequencing, error recovery, context management, and deciding when to retry. It does this every time you use it. It reads files, runs commands, edits code, recovers from errors, and decides what to do next, all without you writing a single line of orchestration logic.

The Claude Agent SDK exposes this runtime programmatically. Instead of building your own agent loop with a framework and then spending days debugging edge cases in your orchestration code, you get the same loop that powers Claude Code, accessible from Python.

This shifts the job from building the loop to describing the workflow. The model decides tool order and error handling, not your code. Your job is to tell it what to do and give it the tools to do it.

Stage 1: Start in the CLI, not the IDE

Most people know Claude Code as a coding assistant. You run claude in your terminal, describe what you want, and it writes code for you. But the same CLI that edits your files and runs your tests is also an agent prototyping environment. It reads your project’s CLAUDE.md for instructions, connects to MCP tools, and executes multi-step workflows. That makes it the ideal place to build and test agent behavior before writing any application code.

Before writing any code, I write what the agent should know and do. The vehicle for this is CLAUDE.md, a natural language file that defines the agent’s identity, workflow steps, tool usage patterns, output format, and constraints. It’s the agent’s brain, written in prose rather than Python.

Here’s a real example from a monitoring agent I built (commit):

## Workflow

1. **Get datetime** — Use mcp__datetime__get_datetime

2. **Retrieve memories** — Use mcp__mem0__search_memories

3. **Identify monitoring condition** — What to watch, what "met" means

4. **Search intelligently** — Use mcp__perplexity__perplexity_search

5. **Store new findings** — Use mcp__mem0__add_memory if new patterns discovered

6. **Return structured output** — JSON formatThis looks deceptively simple. It’s a numbered list. But it encodes the entire decision-making flow of the agent: what tools to call, in what order, under what conditions, and what to do with the results. The agent reads this and follows it, adapting at each step based on what it finds.

The key insight is that most agent behavior is prompt engineering, not software engineering. The CLAUDE.md is where you get the behavior right, and the right place to iterate on it is in a conversational loop with the claude CLI, not in a Python debugger. You run claude, give it a task, watch what it does, tweak the CLAUDE.md, and repeat. The feedback loop is fast because there’s no code to compile or deploy. You’re just editing a text file and having a conversation.

Get the behavior right here. Everything after this is just making it run without you in the loop.

Stage 2: Add capabilities via MCP

Once the workflow is solid, the agent needs tools. The Model Context Protocol (MCP) lets you plug in capabilities without writing integration code. You declare what’s available in a .mcp.json file, and the agent discovers and uses those tools at runtime.

Here’s the config that gives my monitoring agent search, memory, and datetime capabilities. Three tools, zero lines of Python:

{

"mcpServers": {

"datetime": {

"command": "uvx",

"args": ["mcp-datetime"]

},

"mem0": {

"command": "uvx",

"args": ["mem0-mcp-server"],

"env": { "MEM0_DEFAULT_USER_ID": "local-debug" }

},

"perplexity": {

"type": "stdio",

"command": "npx",

"args": ["-y", "@perplexity-ai/mcp-server"]

}

}

}At this point I’m still testing in the CLI. The agent can now search the web, remember findings across sessions, and check the current date, all orchestrated by the CLAUDE.md workflow. I still haven’t opened an IDE.

The important thing to notice is what I’m not doing. I’m not writing code that says “if the user asks about weather, call the search tool.” I’m declaring what tools exist and letting the model decide when to use them. Tool selection at runtime is the model’s job. You declare what’s available, not when to call what. This is the fundamental difference between the inside-out approach and traditional framework-driven development, where you’d write explicit conditional logic for every tool invocation.

Stage 3: Claude Agent SDK — make it a service

The agent works interactively. Now I need it to run as a service, accepting requests over HTTP and returning structured responses. This is where Python enters the picture, via the Claude Agent SDK.

Here’s what the first version looked like (commit, condensed but representative of the ~140-line reality):

from claude_agent_sdk import query, ClaudeAgentOptions, ResultMessage, AssistantMessage

from fastapi import FastAPI

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field

app = FastAPI(title="Torale Monitoring Agent")

@app.post("/monitor", response_model=MonitoringResponse)

async def monitor(request: MonitoringRequest) -> MonitoringResponse:

options = ClaudeAgentOptions(

system_prompt=system_prompt,

setting_sources=["project"],

permission_mode="bypassPermissions",

model="claude-haiku-4-5-20251001",

cwd=str(project_dir),

output_format={

"type": "json_schema",

"schema": MonitoringResponse.model_json_schema()

}

)

result = None

processed_message_ids = set()

async for message in query(prompt=request.task_description, options=options):

# ~60 lines of message type checking, tool use logging,

# cost tracking with message ID dedup, structured output

# extraction, error handling...

return resultIt works. But look at what’s mine versus what’s plumbing. The parts that define this specific agent (the system prompt, the Pydantic output model, the model choice) account for roughly 20 lines. The remaining 120 lines are message iteration, cost deduplication by message ID, FastAPI wiring, and error fallback logic. Every agent I build needs that same 120 lines, and it’s identical every time.

This is the moment where you feel the weight of the boilerplate. The SDK gives you a powerful async generator, but you still have to write the loop that consumes it, track costs, log steps, handle errors, and wire it all up to an HTTP endpoint. None of that is your agent’s logic. It’s infrastructure.

Stage 4: FastHarness — extract the pattern

There’s an old rule of thumb: the third time you write the same code, extract it. After building a few agents with identical plumbing, I extracted the pattern into FastHarness.

The same agent, rewritten (commit):

from fastharness import FastHarness, CostTracker, ConsoleStepLogger

from fastharness.client import HarnessClient

from fastharness.core.context import AgentContext

from fastharness.core.skill import Skill

harness = FastHarness(

name="torale-agent",

description="Torale search monitoring agent",

version="0.1.0",

url="http://localhost:8000"

)

cost_tracker = CostTracker(warn_threshold_usd=0.50, error_threshold_usd=2.00)

@harness.agentloop(

name="monitoring-agent",

description="Monitors conditions via search and returns structured reports",

skills=[Skill(id="monitor", name="Monitor", description="Search monitoring agent")],

system_prompt=SYSTEM_PROMPT,

model="claude-haiku-4-5-20251001",

output_format={

"type": "json_schema",

"schema": MonitoringResponse.model_json_schema()

},

)

async def monitor(prompt: str, ctx: AgentContext, client: HarnessClient):

client.step_logger = ConsoleStepLogger()

client.telemetry_callbacks.append(cost_tracker)

return await client.run(prompt)

app = harness.app141 lines down to 70. The @harness.agentloop decorator handles FastAPI/A2A protocol wiring, the async message iteration loop, message ID deduplication for cost tracking, step logging for tool calls and assistant messages, structured output extraction and validation, and automatic loading of CLAUDE.md and .mcp.json from the project directory.

What remains is what’s actually mine: the agent name, the system prompt, the output schema, the cost thresholds. Everything else is handled.

FastHarness isn’t the point of this post. It’s just the natural conclusion of the process. When you build agents inside out, you eventually notice that the outer layers are the same every time. Extracting them is inevitable.

The inside-out method

The process, in full:

- Behavior (CLAUDE.md) — Define what the agent knows and does, in natural language. Iterate in the CLI until the workflow is right.

- Capabilities (MCP) — Declare the tools the agent can use. Still no code. Test in the CLI.

- Code (Claude Agent SDK) — Wrap the agent in Python to run it as a service. Write the message loop, cost tracking, HTTP wiring.

- Convenience (library) — Extract the repeated plumbing into a reusable harness. Keep only what’s unique to your agent.

Each stage moves outward from the core, from the agent’s behavior to the infrastructure that serves it. The less code you write, the more of what remains is actually your agent. The 20 lines that define what the agent does matter more than the 120 lines that run it.

The hard part of building agents isn’t the code. It’s getting the behavior right. Spend your time there.

Related Posts

Agent Drift: How Autonomous AI Agents Lose the Plot

Autonomous AI agents degrade over long-horizon tasks through accumulated context pollution, not single failures. What agent drift is, why it happens, and how to architect against it.

Repowire: Multi-Agent Coding Workflow Across Repos

Repowire is a pull-based mesh network that lets Claude Code sessions communicate across repositories in real-time, replacing stale docs with live agent-to-agent queries.

The Vibe Bottleneck: AI Coding Workflow Across Multi-Repo

Multi-repo coding agent workflows turn you into the message bus. When work spans repositories, you become the slowdown and the source of errors.